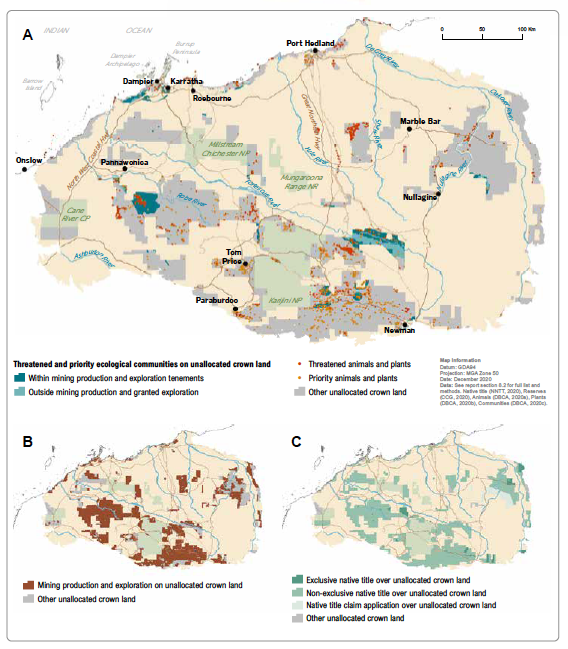

About a quarter of the Pilbara (24%, 4.3 million hectares) is classified as unallocated crown land (UCL) – land in which ‘no proprietary interest other than native title is known to exist’. This includes former pastoral leases covering 3.5% of the Pilbara (0.7 million hectares) that have been earmarked for future conservation reserves, some of which are proposed national parks under Plan for Our Parks.

Fourteen of these ecological communities have more than 20% of their total extent on UCL, including the following priority 1 communities: Brockman Iron cracking clay communities, Bungaroo, Coolibah – Lignum Flats, sub-type 2, Robe Valley Pisolitic Hills, Roebourne Plains gilgai grasslands, Weeli Wolli, West Angelas, Fortescue Marsh, Coastal dune native tussock grassland and Narbung Land System.

About 0.5 million hectares (11.5% of the UCL estate) have been identified as an investment hotspot for the Pilbara Environmental Offsets Fund. The offset potential on UCL has been constrained by the extent of mining and exploration leases (71%) and industry aspirations for future mines.

Despite high conservation and cultural values, the UCL estate is not comprehensively managed for these values. Administered under the Land Administration Act 1997 by the Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage, there are no legislated requirements for conservation management, no publicly available relevant policies, and no management plans for properties with high values.

There is an increasing focus on fire management and some ‘good neighbour’ focus on controlling wild dogs, dingoes and feral herbivores. A 2018 Auditor General report found that contamination on UCL across the state was not being ‘managed effectively’. Contamination sources include tailings dumps from mining and chemical storage and disposal. One of the worst contaminated sites in the Pilbara – the largest in the southern hemisphere – is the former asbestos mining site at Wittenoom (adjacent to Karijini National Park). The former leasehold properties acquired for conservation reserves are managed by the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. These properties are being rehabilitated, initially by destocking, removal of artificial water points, fencing repairs and upgrades to keep out stock, and feral animal and weed control.

Conservation opportunities

Indigenous-led conservation management

The recognition of native title over 90% of the UCL estate provides a strong basis for bringing these lands under cultural land management by Traditional Owners. The emerging capacity for large-scale Indigenous land management in the Pilbara requires support for Indigenous rangers and healthy country planning, and facilitation of access where it has been unnecessarily impeded by mining companies. UCL also offers potential for the establishment of Indigenous protected areas. Establishing formal joint management arrangements on UCL areas with high conservation values would facilitate conservation and constrain harmful uses. UCL is inherently vulnerable to being converted to other tenures that could undermine (or strengthen) conservation management. For example, pastoralists have proposed joint venture arrangements with native title holders to facilitate UCL being converted to pastoral lease. In neighbouring Kimberley and desert regions, cultural land management is now well established on UCL, with recognition that Traditional Owners are present, willing and capable land managers who have rights to use their land. These groups have strong cultural ties to Pilbara Traditional Owners and faced similar challenges in re-establishing cultural land management. They can be of great assistance in the Pilbara by information exchange and mentoring – at forums such as the Indigenous Desert Alliance and the Kimberley Ranger Forum.

Conservation of significant species and sites

The high prevalence of threatened and priority species and ecological communities on the UCL estate makes it a high priority for conservation projects. Some work could be funded by the Environmental Offsets Fund, although this is constrained by the extent of mining. There may be opportunities for project partnerships between Traditional Owners, the government and researchers.

Threat management

The priority threats requiring management on UCL are undoubtedly invasive animals, weeds and fire. Much of this work could be contracted to Indigenous ranger teams.

Rehabilitation and water quality monitoring

Mining has been and remains extensive across the UCL estate, leaving a multitude of sites requiring rehabilitation, including tailings dams and drill rig sites. Some of this work could be contracted to Indigenous rangers. Landscape rehabilitation has been recognised as ‘an obvious area for Aboriginal employment’ in the Pilbara, with both economic and cultural benefits. Indigenous rangers could also be contracted by mining companies to monitor water quality, in watercourses and water monitoring bores, thus improving the credibility of monitoring programs.

Nature, cultural and geological tourism

The UCL estate, much of which is scenic, could provide opportunities to establish tourism businesses. A survey by the Western Australia Indigenous Tourism Operators Council identified considerable potential to expand Indigenous-operated tourism ventures in the state. While 20% of leisure visitors had participated in an ‘Aboriginal cultural experience’, 66% indicated they would do so if it was readily available. One initiative, supported by Tourism WA, is a ‘Camping with Custodians’ program to provide activities and accommodation on land around national parks in the Pilbara. Tourism ventures operated by Traditional Owners could help fund conservation and cultural land management. Tourism opportunities unique to the Pilbara include those focused on its ancient and diverse geology – likely to qualify the region as a UNESCO Global Geopark. Geoparks are intended to foster the protection and sustainable use of geological heritage and promote the economic wellbeing of people who live there. Such a designation would undoubtedly increase the geotourism appeal of the Pilbara. In China, the geotourism revenue of 8 geoparks tripled in the 4 years after their creation. Some geotourism promotion already occurs in the Pilbara, with the Discovery Trails to Early Earth guide featuring 6 drive trails.